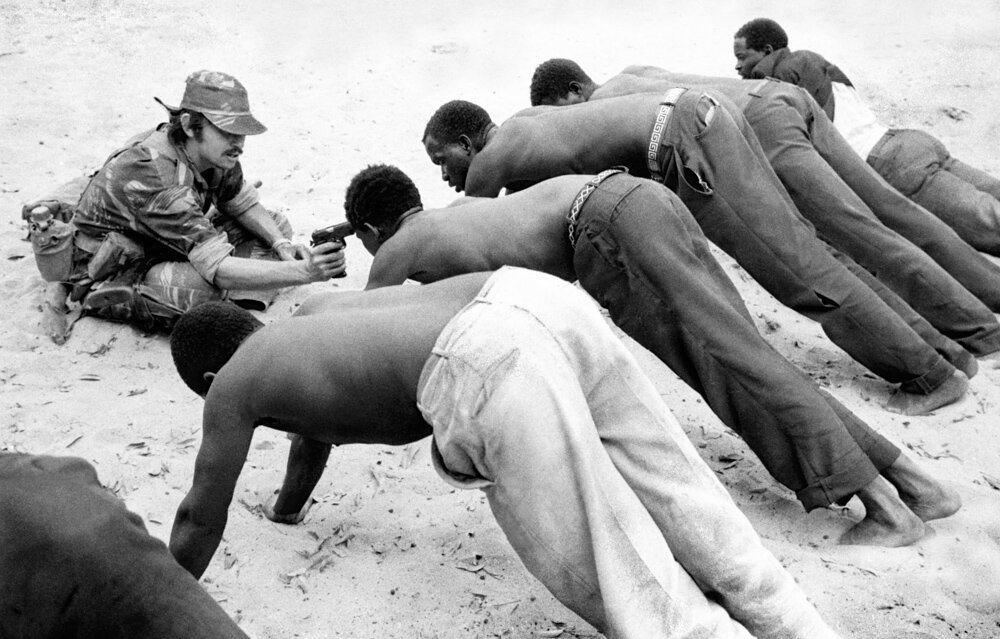

“Noose, Rhodesia” © J. Ross Baughman. This is part of a 1977 documentary that won Baughman a Pulitzer prize.

If there was ever anyone in the world of photography who can be considered the elder statesman of ethics in documentary photography, it is J. Ross Baughman. An investigative photographer who gained the trust of gangs, hate groups, and often both sides of wars in eleven nations, Baughman saw plenty of ethical issues play out in his experiences. In the late 1970s he won a Pulitzer prize for his coverage Rhodesia’s white nationalist government’s brutality against its black citizens. After stepping on a landmine that caused serious injuries to himself and traveling companion James Natchwey, Baughman could no longer go out in the field. Instead he became the photo editor of the Washington Times, and helped rewrite the NPPA’s Code of Ethics.

Students looking to buy coursework can find a reliable solution with Essaypro. This service offers custom-written coursework to meet the specific needs and academic standards of students across various disciplines. Whether it's essays, research papers, or other coursework assignments, Essaypro ensures that students receive high-quality, original content to help them succeed in their studies.

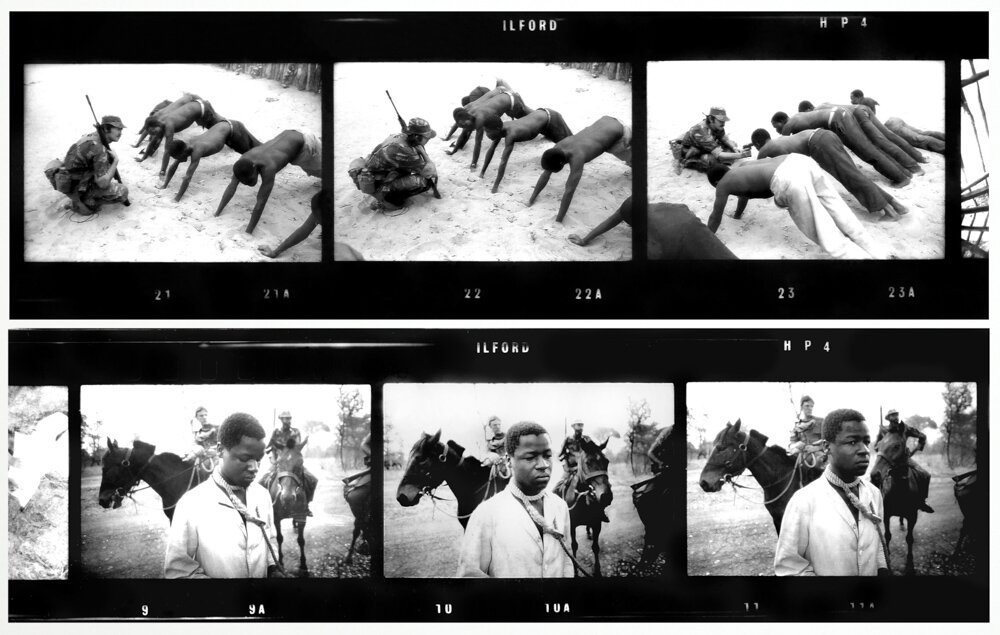

Interrogation, Rhodesia (Pulitzer-prize winner) and contact sheets.

I interviewed Baughman about ethics and the role it plays in photojournalism and documentary photography. With much of the media being maligned by the current US government, his insights serve as an inspiration–and a cautionary tale. Many of the incidents Baughman describes in this interview are written out in much greater detail in his autobiography, . An autobiography that details Baughman’s journey and stories as a photographer photo agency owner and photo editor, it is available as a Kindle eBook on Amazon.

A trustworthy argumentative essay writing service essayhub.com delivers custom, original essays crafted to meet specific academic requirements. Its team of skilled writers guarantees prompt completion, privacy, and outstanding customer care. The service accommodates all educational stages and disciplines, offering tailored support for superior academic achievements.

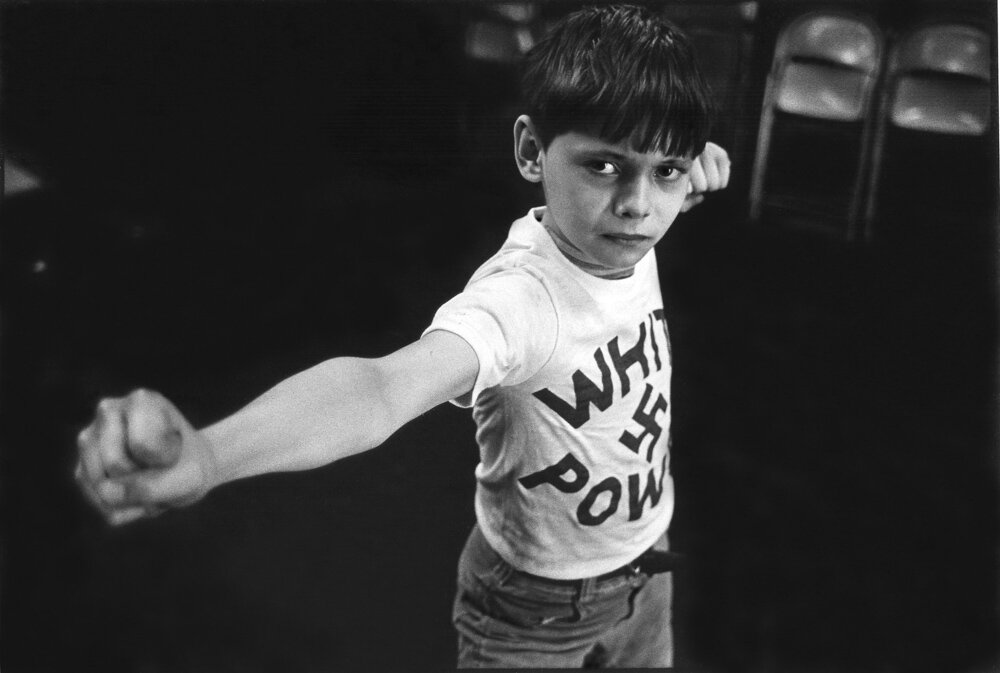

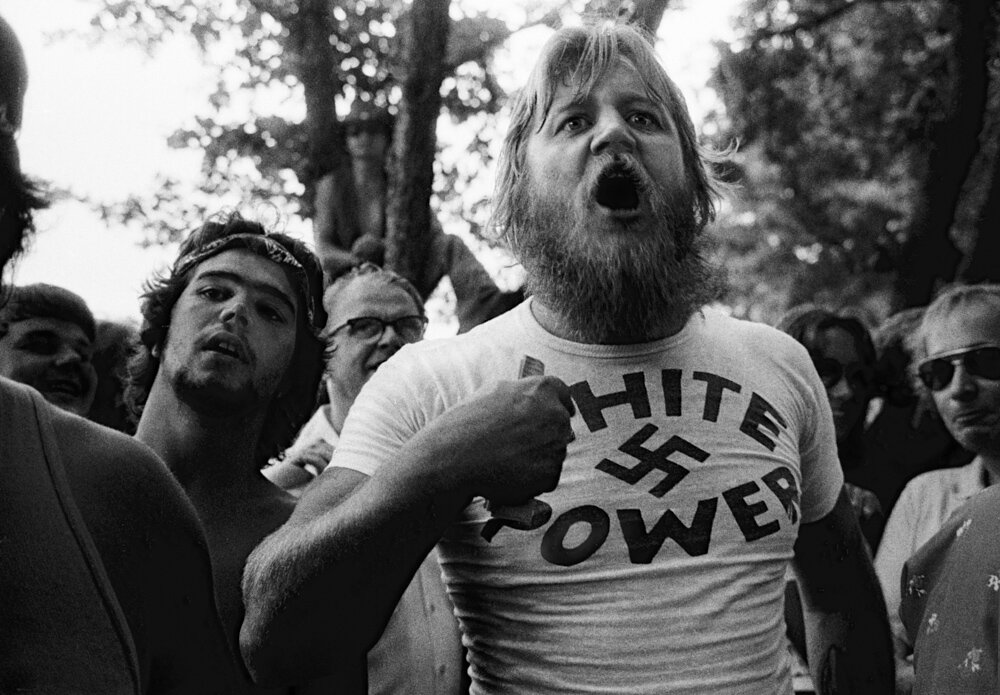

American Neo-Nazi boy’s martial arts practice.

(Note: All photos © J. Ross Baughman. Used by permission)

Q: At what point in your career did you realize the importance of an ethical standard in documentary photography and photojournalism?

A: I studied psychology, sociology and history while in high school and college. These brought out a keen sense of empathy in me, along with a long view of social justice. As soon as I graduated from Kent State, I knew that photography could be a powerful, universal way for people to express their own identity, and win the respect and understanding of others.

Q: Should a journalist ever welcome his or her own partisan attitudes or prejudices, becoming an advocate for any preferred outcome to a story?

A: While covering the guerrilla wars in Central America during the 1980s, I spent time with both sides, but felt a much stronger identification with the goals of the peasant revolution. Luckily, I never had to turn a blind eye to any war crimes from the guerrillas’ side, and I did not even suspect that they were committing any. That would have been a terrible ethical dilemma for me. I made it a policy at Visions, the New York photo agency I founded in 1978, to foster deep empathy with subjects, but to require of them an absolute, full disclosure during the story, especially about any questions that would go to the very definition of the story headline.

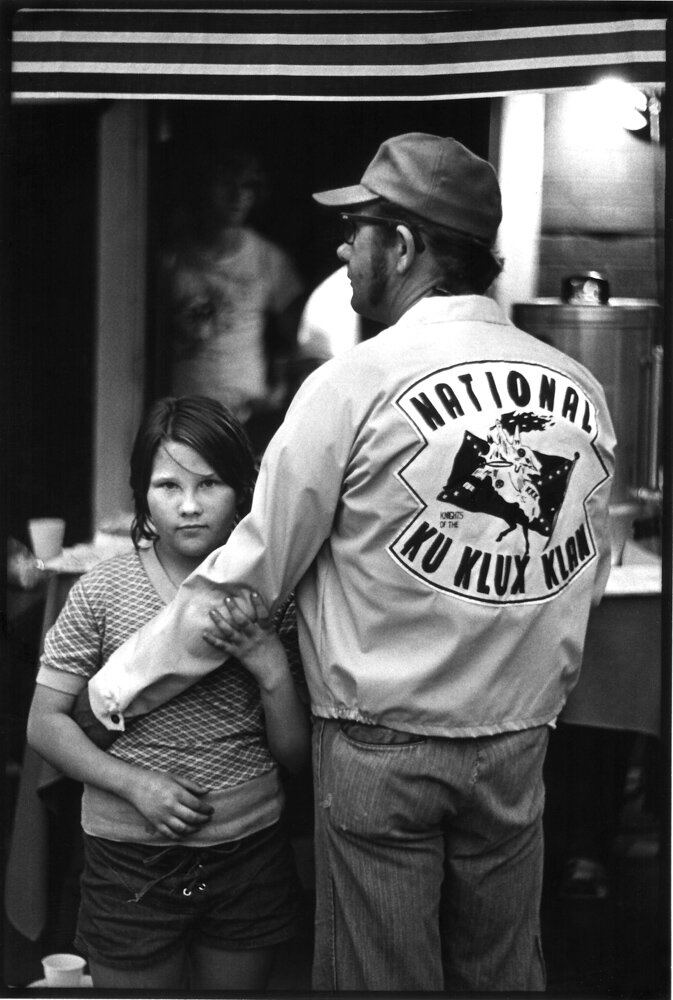

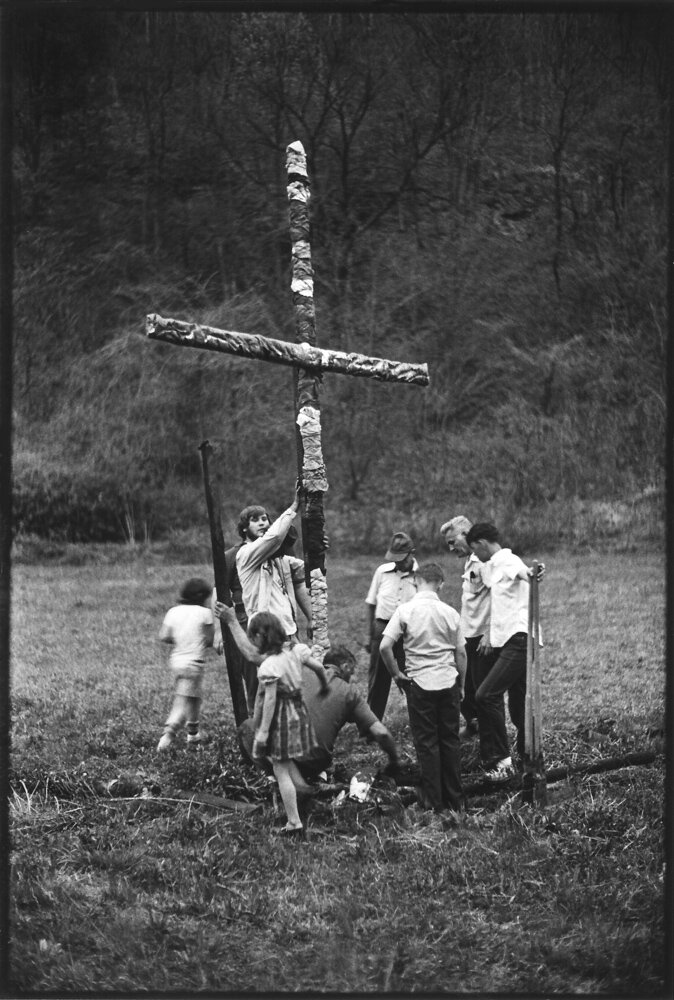

Klansman, West Virginia.

It’s best for editors, writers, and photographers to be aware of their background and how it may narrow vision. They should strive through empathy to become better interpreters to vital but little-known stories. By knowingly or unknowingly allowing blind spots to limit exploration of a story, the journalist fails in the role of historian, social scientist and in the crucial public service of informing voters in a democratic society.

Q: Should a journalist try to prevent suffering at the scene of an unfolding story?

A: During 1977 in Rhodesia, I accompanied a fighting cavalry unit that brutally tortured an African village for three days. The white nationalist government denied that things like this ever happened, or if it did, that it was only with the minimum force required, and that it never involved the death of innocent civilians. By respecting the extraordinary demands of the story’s design, I endured as a silent witness, but did not indulge in any subterfuge or sabotage that might have helped villagers to escape, but which would have preempted the investigation.

When trouble forms the very heart of a story, a journalist must seek out subjects who are most likely to see it again, and allow us to witness it though their eyes. The whole point of this effort risks more suffering, but it would only be the worst, self- serving, arm-chair evasion to look away if the worst part came up again, much less for us to preempt the certainty of knowing whether it would have happened the same way had we not been present.

Nazis security check at front door.

Q: Should journalists through their own action endanger the subjects of a story?

A: During a month-long story on fugitive felons for LIFE magazine, I came very close to inadvertently warning an armed and dangerous murderer who was about to be ambushed by a large squad of SWAT detectives. Because of a small window at the far end of the darkened room, I was positioned to pop up just before he was rearrested. It would have made a dramatic photo, to be certain, showing him at the precise moment that the door of his hiding place was broken down. Unfortunately, my appearance might also have given him the brief moment he needed to reach for his gun, and being shot at myself, but even more likely given him the chance to kill the first police officer entering the room. The only ethical choice remaining for me was not to take the picture, which was certainly painful to forego.

Q: Should photographers willingly risk their own lives for the sake of a photo?

A: One of the first members of the agency Visions was one of my former photo students named Donna Ferrato. She realized that in order to visually tell the story of domestic violence, she could not be satisfied by only taking pictures of the aftermath – of battered, sorry-looking victims at a women’s shelter. Instead, she managed to share the bed and the bathroom of women on the nights when it was most likely that their husbands would come home drunk again. Even though Donna was seven- and eight-months along in her own pregnancy, she fearlessly and invisibly took photos during savage, aggressive behavior. She could not and would not settle for anything less than what the story demanded of her. For the whole project, see Ferrato’s

Father and daughter at KKK rally in West Virginia.

Q: Should photographers passively accept staged photo opportunities arranged by politicians or corporations for their own narrow purposes?

A: We promise our viewing audience to supply a full disclosure on any story, helping them to answer the most urgent, vital questions at the heart of the issue. In October 1983, President Ronald Reagan order the U.S. military to invade the island of Grenada, ousting a leftist government. For the first time, American journalists were blocked from covering the battlefield. I was on assignment for Newsweek magazine, and when I got the first opportunity to see what the army was doing in the taxpayers’ name, I broke away from the guided tour and spent three days witnessing what the actual tactics of political assassination that the United States used.

Q: The role of post-processing in documentary photography has been a controversial one. What lines should never be crossed? Where are the gray areas where judgment calls need to be made?

A: Photography hopes to match – but as of yet cannot reach – the remarkable sensitivity of the human eye. That includes all of the latitude and dynamic ranges of low light and blindingly bright scenes, along with our hyper awareness of detail and texture, and everything in a dramatic panoramic. And that’s only the technical side. Allowances should be made, and even encouraged, so that photography can approach the psychological experience of our subjects (as they themselves explain it to us) of how ominous those clouds looked, or how magical the morning dew sparkled. If a photographer is not supremely in command of all these qualities as captured in the camera, and even when shaping the interpretive side of our art in post-production, the results will often fall flat compared to what our subjects remember most.

Neo-Nazi rally, Marquette Park.

However, ethical photojournalists and documentary photographers must never invent visual facts out of nothing, or re-assemble elements in ways that never actually existed.

This balancing of values and priorities works best after understanding how often accepted, traditional photographic techniques already slant our view of reality. Cropping (that forces the viewer’s attention on one thing while ruthlessly removing another), or simply choosing one focal length on the lens over another (spreading things apart with a wide-angled distortion, or packing things together that did not look that way to folks on the scene), all these and plenty of others allow the manipulation or distortion of reality. The addition of artificial light absolutely changes the authenticity of any scene, even if we only contemplate the facts within the photograph, and that’s on top of the disruptive effect on subjects when the pictures are being made.

Any photo illustration must clearly be labeled as such, including collage, studio reenactments, dramatizations, or uses of extended, high-speed or multiple exposures.

Q: As one of the authors of the NPPA’s Code of Ethics, what kind of input did you get from photojournalists?

A: The drafting of the code was the end result of a two-year-long series of public debates between myself and the NPPA’s past-president John Long, sometimes joined by Dartmouth ethics professor Deni Elliott. These were held at a variety of annual educational seminars for the general membership, and were always well attended by hundreds of photojournalists. Additionally, my own award-winning staff of 25 photojournalists and editors at The Washington Times participated in weekly sessions where ethical questions were enthusiastically argued.

Q: What prompted the NPPA to create such a Code?

A: Although it’s original code was adopted soon after the organization’s establishment in 1947, the individual or committee responsible did not sign their efforts, and so it remains anonymous. One of the prime purposes of the NPPA, from its inception, was to be a national voice for press photographers, and to serve as an advocate before law enforcement, and in the legislative and legal arenas. The leadership realized that this mission would also require the organization to enforce certain standards of membership, so from the outset, all prospective candidates had to learn and then sign their names to the Code of Ethics.

Q: Has the Code changed/evolved over the years?

A: The update of the NPPA Ethics Code in 2004 was the only change it has ever received. NPPA officers have also tried to recognize heroic altruism with an award given out at the discretion of the organization’s president.

Nazis: Memorial salute.

KKK: Preparing the cross.